Having an awareness of and understanding what systemic racism is and how it impacts the lives of Black families across the board is an important first step to breaking down barriers, supporting families and beginning the work of dismantling racism. While we may not solve a problem 400-years old, we each can work towards self-improvement and community engagement.

TYPES OF SYSTEMIC RACISM

- Structural: Social, economic, or political systems featuring public policies and practices, cultural representations and other norms that perpetuate inequities.

- Institutional: The policies and practices within and across institutions such as schools or healthcare entities, that put certain racial groups at a disadvantage.

- Explicit/Implicit Bias: Face to face or covert actions toward a person or persons that express racial prejudice, hate or bias.

SYSTEMIC RACISM

- Lack of awareness of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare

- Lack of skills and knowledge of culturally competent care

- Unequal treatment due to implicit bias, stereotyping and prejudice

- Trust of healthcare system due to historical systemic injustices

Systemic

Racism

Explained

Health Disparities

Differences or inequalities in health care status due to gender, race/ethnicity, education, disability, geographic location, or sexual orientation.

Examples of Health Disparities

- Children from racially/ethnically diverse backgrounds are less likely to:

- Be screened early

- Have follow-up evaluations when they “fail” a screen

- Get an early diagnosis

- Access early services

- Non-Hispanic white children were 30% more likely to be identified with ASD than non-Hispanic Black children & 50% more likely to be identified than Hispanic children

Source: Massachusetts Act Early: Considering Culture in Autism and HRSA: National ASD Data

- African American, Asian and Hispanics have more chronic disease, cancer and infections.

- African American women are more likely to die of breast cancer than any other racial group.

- Rural residents have more chronic conditions such as diabetes and are more likely to die of heart attacks.

Source: Youth Health Services Corps, CT

Health Equity

According to the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation:

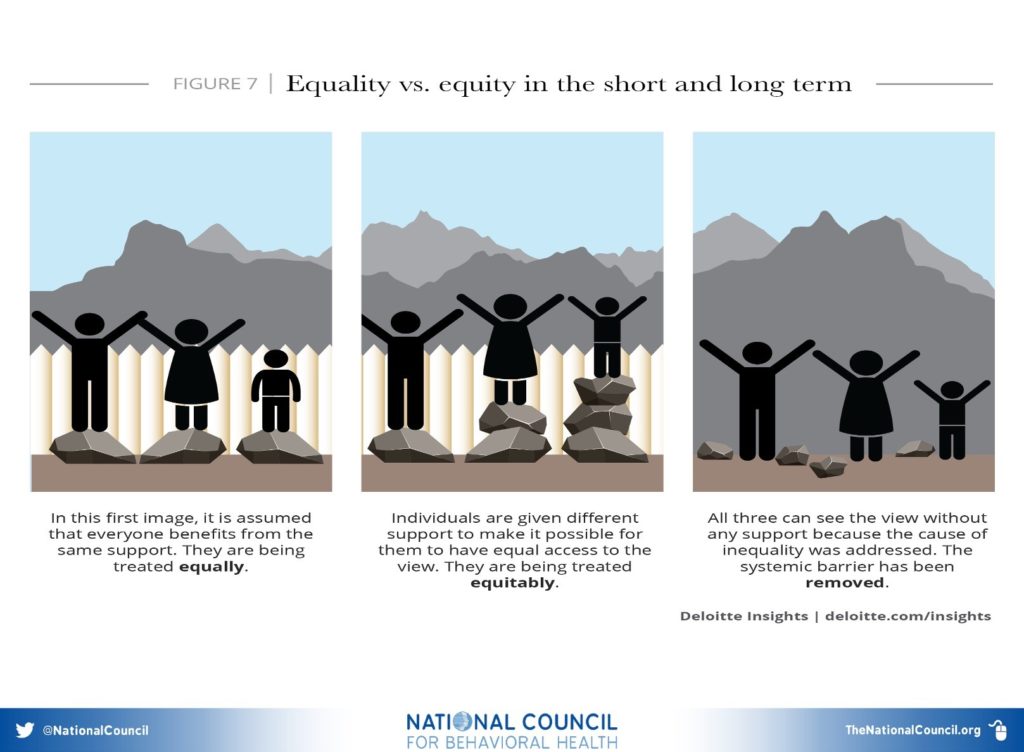

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.

The following should be added when the definition is used to guide measurement; without measurement, there is no accountability: For the purposes of measurement, health equity means reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and its determinants that adversely affect excluded or marginalized groups.

Health equity, as seen through the lens of the family with a child with special health care needs, is especially important, and not without additional challenges. How do we ensure that all families have access to the health care they need for their child with special needs, as well as the resources to pay for it?

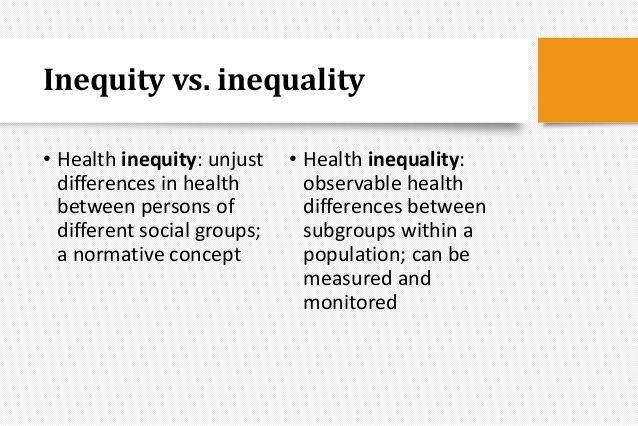

Equity vs. Equality

Impact on Black Children and Youth

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “Racism is a core social determinant of health that is a driver of health inequities. The impact of racism has been linked to birth disparities and mental health problems in children and adolescents.”

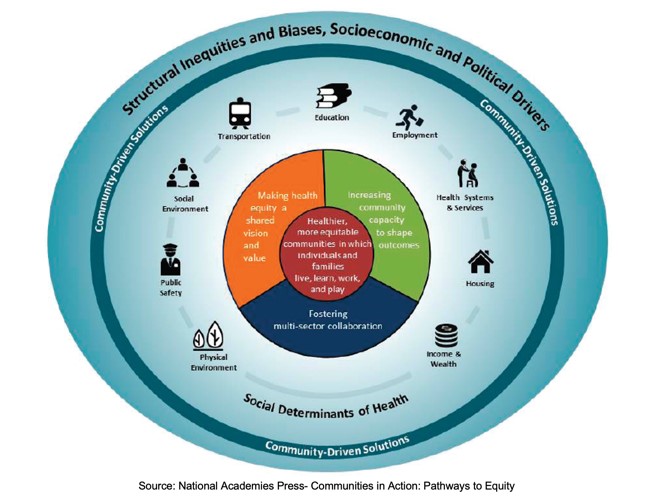

The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine’s Pathways to Equity further highlights how social determinants of health has lasting implications on young children especially those from low income and minority communities:

“Poverty, food insecurity, lack of stable housing, and lack of access to high-quality and developmentally optimal early childhood education are among the childhood factors that contribute to “chronic adult illnesses and to the intergenerational perpetuation of poverty and ill health found in many communities (e.g., obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, poor educational outcomes, unemployment, poverty, early death)” (AAP, 2010, p. 839).

Young children are most likely to live in poverty, and children from low-income and minority communities are most vulnerable (Burd-Sharps and Lewis, 2015). The nation’s growing racial and ethnic diversity, coupled with the conditions that lead to serious early life disadvantage, have serious implications for health and health disparities in later life, leading to squandering human lives and their potential (OECD, 2009).”

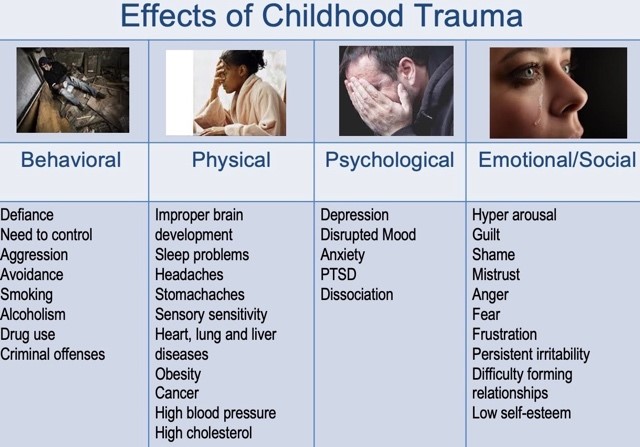

Marginalized children and youth of color whose lives are affected by social determinants, systemic racism and intersection’s such as disability, face even bigger barriers and trauma that often lead to behavioral, physical, psychological and emotional/social concerns that affect all aspects of their lives including school.

To dig a little deeper visit “Explore More” block: Click on videos to watch Episode 2 of “Understanding Racial and Social Injustice, youth edition” to learn how racism affects youth.

More about the impact of racism on Black children and youth

|

More Resources:HOPE as an Anti-Racism Framework in Action is a resource paper that addresses racial disparities in systems that serve children and families. The resource walks you through scenarios that disproportionally affect Black and Brown children and youth and then offers steps to work through each problem and consider system and policy changes. |

Intersectionality

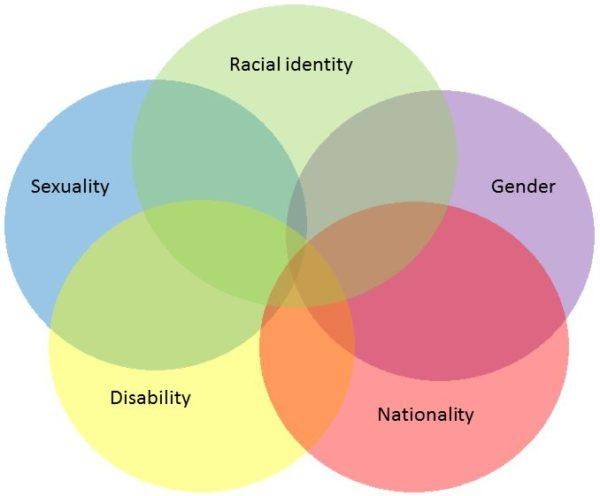

UCLA/Colombia Professor of Law, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, is widely known for coining the term “Intersectionality” and bringing the concept to wider attention.

She describes intersectionality as “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times, that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things.” (Columbia Law News)

According to the National Association of School Psychologists:

Intersectionality describes the merging or intersection of marginalized identities. Members of historically oppressed communities such as African American/Black, Hispanic/ Latino, LGBTQIS, women, disability, have experienced discrimination. Holding one of these identities often results in facing discrimination. When these identities intersect, the likelihood of discrimination and oppression increases exponentially. Such experiences are distinct and often more intense than those related to a single marginalized identity and can magnify social and economic disadvantage.

As family organizations it is important for us to recognize and be aware of intersectionality as it reflects the experiences of our most marginalized children and families.

What is

intersectionality?

How to Address These Challenges

DATA COLLECTION

Health Equity Solutions states that: “The collection of race, ethnicity and language (REL) data is a critical component of evaluating health outcomes among various populations and ensuring health equity for everyone. In many cases, we do not fully know the extent of these disparities due to a lack of timely and actionable data on specific populations. To achieve health equity and ensure that everyone has the opportunity to be and stay healthy, we must move toward having the data necessary to target interventions. The lack of uniformity and limited access to timely data on socio-demographic factors, the most salient being race, ethnicity, and language (REL), represents a serious challenge to achieving equity.”

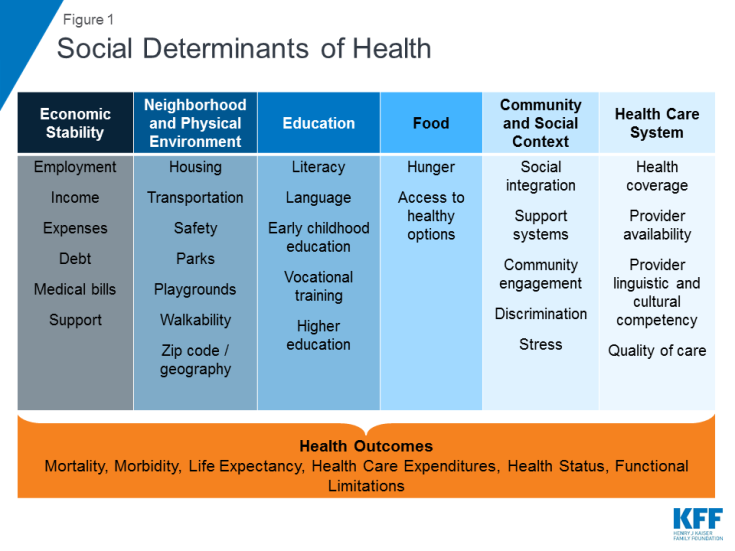

UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF):

Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.1They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care.

Family Organizations

Leading the Way

Family Voices, Family to Family Health Information Centers, Parent to Parent and other family organizations can be powerful allies for families in advocating to address health disparities to improve health outcomes.

They can address health disparities by:

- Developing and participating in cultural awareness and sensitivity training

- Identifying community specific disparities and key social determinants of health contributing to them

- Recognizing specificity of community needs and priorities

- Develop a community health and family centered perspective in addressing disparities

- Engage local health systems to get access to race, ethnicity and language (REL) data

- Design community-driven, community-led communication, programs and initiatives in partnership with trusted leaders or cultural brokers

- Collaborate with other family organizations to harness resources and information.

Understanding systemic racism, health disparities and the impact on Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) can inform our work and help us to advocate for the families that we serve.